modeling a horse race

abstract approaches to liberalism and conservatism

I have the distinct pleasure of teaching a course this semester on how liberalism and conservatism shaped American history. Part of the difficulty of teaching this subject is in helping students understand how and why the underlying concepts change over time. This presents an interesting “teaching methods” challenge that I’ve contemplated throughout the semester and struggled to find a good solution for.

I view this fundamentally as a definitional problem: it’s hard to pin down a comprehensive meaning for liberalism or conservatism, partly because of the long, complex history of the two traditions, partly because of the mixing of theories that practical politics tends to effectuate. These are ideas in motion. Neither set of ideas fit neatly into categories - each constitutes a theory of government, to be sure, but also a framework for applied policymaking, a literary and epistemic tradition, and an ideology for democratic politics. Early in the class, we tackled this by building mind maps of both concepts, establishing links and anti-links to gain a better understanding of each theory’s tenets and how they related to each other. Recurring themes for liberalism tended to include concepts like change, progress, economic freedom, liberty, and equality, while conservatism usually included tradition, religion, hierarchy, and stability. But this still didn’t account for changes to the ideas over time - that is, why a tenet like “tradition” might look different if you examine how the principle is carried out in the 18th Century as opposed to the 21st Century.

One possible approach I considered was a participatory model where we created actual hats labeled “conservative” and “liberal” that students could wear as part of the classroom activities to think through historical problems from different perspectives, which would, at least in theory, free them from needing to take personal responsibility for challenging world views while allowing us still to derive learning value from these, and which we could introduce more complex sub-variants to as the course progressed (an “economic liberal” hat, for example). I decided against using this as my initial approach, however, because I felt it put too much pressure on students early in the semester - though it may prove a useful activity later on when students are more comfortable with the subject matter.

Another approach, however, would be using heuristics to simplify complex ideas. In law school, I took Trusts and Estates with a remarkable and engaging professor named Howard Erlanger, and part of his teaching method involved approaching complex ideas through a set of “Erlanger’s Paradoxes” - a sort of theoretical shorthand to help students reach analytical conclusions faster given a limited set of facts. These were especially useful when the law neither said what it meant, or meant what it said. “If you don’t know if you have marital property [in Wisconsin],” his first principle stated, “then you do.” I had a chance to sit down with him and pick his brain about my somewhat comparable pedagogical predicament, leading to what I’ve taken to calling, in conscious emulation of my intellectual upstream, “Sig’s Abstractions.”

I’m writing this post in media res (with mixed feelings about my students reading it) because doing so has been helpful in developing these abstractions further, as well as a language to discuss them with my students. It’s important to note, however - and I hope my students understand this - that these are only a shorthand primarily rooted in the American context, and the interpretations of liberalism and conservatism presented here may grate with other academic, especially non-American perspectives on the same.

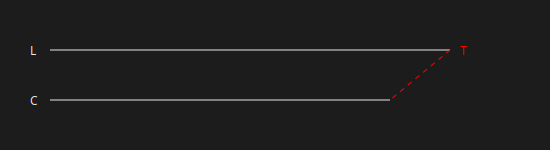

I. The Horse Race

The first problem I’ve experienced in teaching liberalism and conservatism is, put simply, why neither of these ideas look exactly the same as they did in the past. As an example: Adam Smith’s liberalism placed, I think, a far greater emphasis on free markets than today’s liberalism, which has adopted intervention as a core tenet. To square this circle, we would probably need to reach two conclusions: first, that liberalism outpaces conservatism; second, that conservatism is nonetheless also a “moving” idea that changes over time, though probably not at the same pace as liberalism. I find that this is best illustrated by the analogy of a horse race: if liberalism and conservatism were two horses that, for the purpose of the discussion, are situated at the same starting gate, then which horse will outpace the other at any arbitrary time?

If you put your money on liberalism, then you’ve correctly made sense of the analogy. But, a more challenging question: does the fact that liberalism outpaces conservatism mean that the conservatism horse never left the starting post? Of course not. Conservatism generally tries to keep pace with the faster horse, but never passes it because, to convervatives, the race is not necessarily to the fastest. Perhaps, to take this analogy a bit further, conservatism wishes that the race were oriented in the opposite direction, but at the same time doesn’t want to be left too far behind by the faster horse running the other way. Thus, we see conservatism today adopt all manner of ideas that, in the 19th Century, might have seemed alien to those who identified with that label.

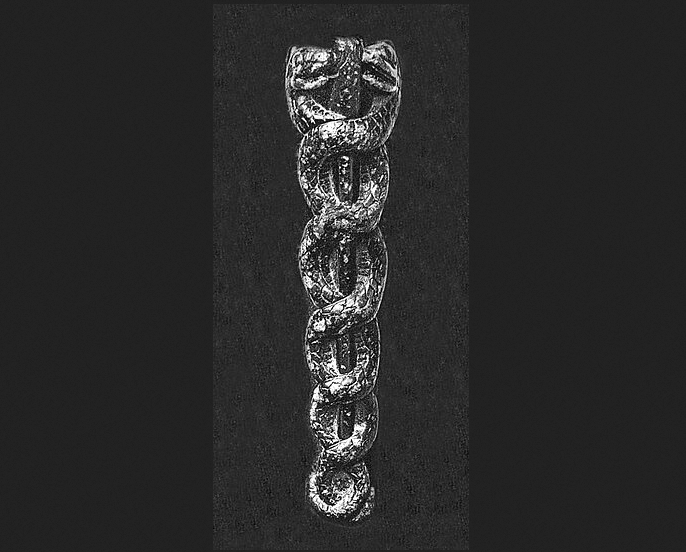

II. The Caduceus

The second teaching problem I’ve experienced is why the two ideas seem sometimes to leverage similar language and ideas, or might be used to justify the same policies, despite differing significantly in their intellectual tradition and worldview. A good way to think about this might be that liberalism and conservatism are not ideas that exist in a vacuum - their scholars read each other’s work and respond to the same events, and intertexts are inevitable when given enough time. A useful way to visualize how concepts might converge is the image of the caduceus, a symbol that depicts two snakes wrapped around a staff and conveys a sense of mediation and diplomacy. Beyond my personal predilection for the classics, I’ve found that students are also interested in the strange symbols from antiquity and think that the novelty of the image helps grab and keep their attention.

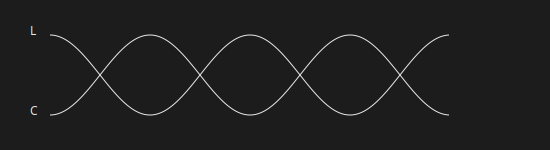

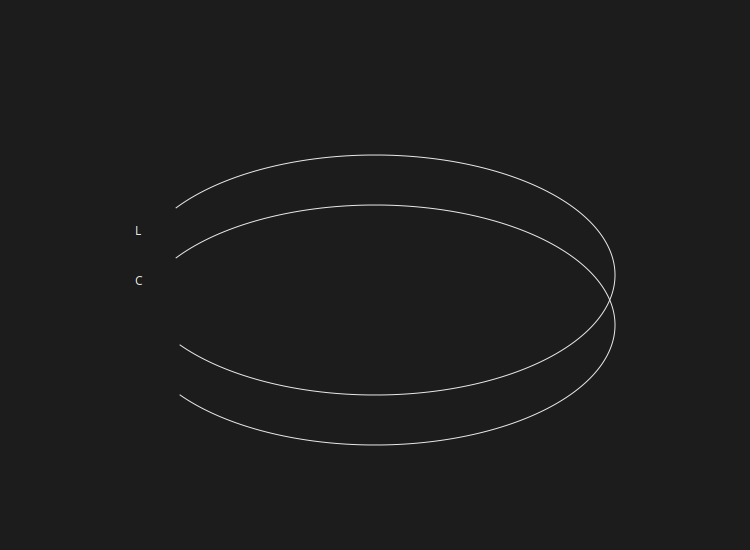

So, in visualizing this idea in a manner similar to the first, we might plot liberalism and conservatism as a wave function and its inverse, with the two waves periodically intersecting with one another.

III. Wedges

The complexities of liberalism and conservatism often produce, not just distinctions between these theories, but also the divergences within each. This phenomenon, which I will here call “wedges,” refers to the internal splits that can occur within a single theoretical framework. This concept stands in contrast to the “caduceus” model described above, where similar language and outcomes emerge from different frameworks. Here, we observe how a single framework can yield different substantive results.

I’ve taken to referring to this phenomenon as liminal divergence, or sometimes issue-based dichotomization if we’d like the emphasize the result instead of the modus, by which I mean cases where individuals or groups that adhere to conservative or liberal principles hold different, often-contradictory positions on substantive policy issues when compared to others that adhere to the same principles. Can a liberal thinker authentically justify (as opposed to cynically, or for political purposes) qualified immunity based on a liberal worldview? Can a conservative thinker justify affirmative action based on a conservative worldview?

These dichotomies, I would argue, don’t emerge solely from the differences between opposing worldviews but rather emerge from the varying emphases on and interpretations of liminal concepts and controversies by individuals who subscribe to the same general political philosophy when they confront real events and issues relevant to their own lives. Here, I use the term “liminal concept” or controversy to describe the fundamental, often contentious ideas that exist at the boundaries or thresholds of a single political philosophy. They might be matters of interpretation, where different scholars approach, accept, or reject them in different ways. They seldom make up the core tenets of that philosophy and, as a result, are left sometimes without solid treatment by the academic community and perhaps willfully ignored by political practitioners. They are neither fully embraced nor entirely rejected by any single ideological group, but instead exist in a state of ambiguity or ambivalence.

What I mean is that it’s not clear that humans are principled creatures per se, even if we often try to appear so. More often, we tend to “window shop” for the principles and procedures that get us what we want.

But what are these liminal controversies? I think there are probably too many to provide an exhaustive list here, but a few might include disagreements over the individual vs. collective, material vs. ideological, outsiders vs. a political establishment, reforming institutions vs. all-out revolution.

IV. The Ouroboros

The previous conceptualizations presume that knowledge, culture, and institutions are constantly moving forward. However, this linear progression doesn’t always hold true in the real world. Ideas don’t just move forward; they also circle back, revisiting and reinterpreting past concepts. This leads us to a third teaching problem: why the ideas often seem to hearken back or revert to past approaches. Admittedly, this phenomenon is something that will become more apparent in discussions of more recent events as we are able to observe how history sometimes “repeats itself.” For example, debates around the First National Bank were largely focused on constitutional interpretation, but later debates were able to leverage experience and history as evidence for or against the bank’s rechartering.

The practice of “hearkening back” might be a less surprising phenomenon for conservatism, which places far greater an emphasis on history and tradition - but even liberalism has a tendency toward archaics. Take, for instance, the resurgence of classical liberal ideas among libertarians. While classical liberalism emphasizes individual liberty and limited government, it’s been reinterpreted and adapted by modern libertarians to address contemporary issues. Whether or not libertarians constitute a Liberal or Conservative group will necessarily invite debate, but what’s clear is that their core tenets draw heavily from early Liberal thought.

I think this idea is nicely modeled by the tail eater (Attic: ὁ οὐροβόρος), another ancient symbol of life, death, and rebirth - or, in a more abstract sense, the cyclicality that permeates all areas of life, to help illustrate how liberalism and conservatism don’t just move forward, but can sometimes hearken to old arrangements.

Represented in the same manner as the earlier concepts, it might look like two circles converging back upon themselves.

In any event, these musings constitute a slightly cleaned up set of working notes that have evolved over the first few weeks of the academic term. Thank you for reading, and hopefully the effort has been rewarding and enjoyable.