how i take notes

and why you should care

As a part of the course I currently teach at the University of Wisconsin called Legal Studies 444: Law in Action, I developed a lesson plan on “taking effective notes for law school (and life)” and have taken to giving this lecture to students early in the semester so that they can (hopefully) apply some of its takeaways as the course develops. Beforehand, I ask them to prepare two readings: first, an essay from GULC emeritus professor Robin West on the path to becoming law faculty; second, the introduction to How to Take Smart Notes by Sönke Ahrens. The point is to encourage them to conceptualize their legal education as both a practical and theoretical endeavor, and their notes as serving both a present and future purpose. I’m including the substance of this lecture in the essay below, and follow this up with a deep-dive into how you can organize your notes using the story of a hypothetical second-year law student, Jade Law.

I. Law as Knowledge Management

If most of what you know about law school comes from television, then you’ll be forgiven for believing that law school is mostly about producing legal practitioners. There’s lots of reasons why this may be the case: legal practice comes with wealth, prestige, and a direct impact on the lives of your clients and society writ large. However, legal practitioners also are simultaneously legal thinkers, especially those who are in roles where they need to conduct research to properly advise their clients. Further, plenty of practicing lawyers engage in outside research and publish this research in their free time, too. Likewise, appellate judges, clerks, and attorneys are all engaging in legal thinking to establish legitimate legal standards, argue their cases, and make sense of the law. So, it’s not clear that legal practitioners constitute a distinct category from legal thinkers.

Given that there’s so much thinking involved in legal practice, we might ask whether law school primarily about producing practicing lawyers or producing legal thinkers. Robin West’s essay is striking in its claim that, to become a competitive candidate for a position as a law professor - which I am employing here as a proxy for the typical legal thinker, one need only write a law review article and take some interdisciplinary classes. Other than that, you’re free to take other classes as usual in law school. Does that make it sound like law schools are primarily focused on legal practice? Of course, there is also a secondary issue of academic performance - law faculty postings are hotly contested. Likewise, the student experience will vary from law school to law school, as some institutions and their faculty might have a greater focus on practical rather than theoretical pursuits. But what West’s essay suggests is that law school is more than a little bit oriented toward legal thought, not just legal practice.

I should briefly note how my own thinking on this subject has developed over time. As a second-year law student at the University of Wisconsin, I took a course on state and local government with Professor Miriam Seifter. Beyond helping me understand legal academia much better, Professor Seifter introduced me to a robust literature on legal culture. In particular, she shared the work of Steven Teles and Amanda Hollis-Brusky on conservative legal networks in the United States, as well as her own scholarship on constitutional communities, as a way of introducing me to some of the informal social structures underpinning the law.

II. Competing Goals and the Slip Box Method

If we accept that the structure of law school is naturally oriented toward legal thought, then we should ask ourselves whether our personal knowledge management systems or note-taking methodologies are sufficient in order to lead us to success in that arena. We need no detailed excursus to understand the range of different ways that people take notes. Many take notes by hand, a few dictate their notes, and some take no notes at all. There are a variety of applications available for digital note taking, like Microsoft Word or OneNote, Google Drive, Evernote, Notion, Confluence, Vim, Emacs, and Notepad - to name only a few. Beyond platforms for note taking, different methods are available to us to organize our notes: we can use a directory hierarchy to keep our notes separate, organize notes by date, or use tags as ways of cross linking notes with overlapping subject matter. The most important takeaway I emphasize to my students is that they have a system that works for them. Indeed, when it comes to taking effective notes, ‘to thine own self be true.’

Sönke Ahrens’ book is helpful in understanding how we can be true to ourselves while also developing a system that is effective. We need to start by asking what our goal is in taking notes. Ahrens distinguishes between planners and experts, where a planner is trying to anticipate demands and orient their knowledge management system to complete those demands. For example, you might plan around completing assignments for a class and getting an A. An expert, on the other hand, is concerned primarily with learning things and becoming masters of their craft. A ‘planning’ goal could be relevant to a student that wants to organize their notes to maximize short-run outcomes, while an ‘expertise’ goal could be relevant to one who wants to organize their notes to maximize long-run outcomes. While I would argue that we should understand these goals as competing with one another, to be sure, and my personal preference is for the ‘expertise’ goal, I understand that students are going to be anxious about their grades. My claim is that you can develop a note taking system that accounts for both goals simultaneously, and that good grades in law school often come down to your effectiveness as an ‘expert’ and not a ‘planner.’

Some of my students shared note taking methods that they use that allow them to interlink ideas and sort them into their short run and long run usefulness. The problem with some of these approaches is generally that they increase in complexity as time progresses and they take lots of time to maintain. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a method that remains simple and scalable over time? This is where the slip-note method, so some variation therein, comes into play. This is a method where you stack new notes on top of each other, and connect them as you go. I like to think of this as ‘knowledge management on the go’. It’s a complex system, to be sure, but not in a way that necessarily grows unmanageable. Rather, it’s conceptually complex and enables increasing complexity of thought, especially when you take notes that span multiple disciplines. It’s not something that you need to get perfect the moment you start it. In fact, those that use it tend to discourage that attitude of perfectionism which can make note taking a very unenjoyable and laborious process.

III. Taking Notes with Obsidian

There are a handful of tools that facilitate the structure I’ve shared above. While many applications will do, my experience is that tools that enable you to tag or link notes with each other are best suited to this method. My preferred app is Obsidian (yes, I am one of those cultists) because it makes it easy to write notes and use tagging systems to link these notes together as you progress, allowing its users to take notes to serve a simultaneous present day purpose and long run purpose without needing to spend substantial time and energy sorting these notes, and without significantly increasing the complexity of managing these notes and organizing them together as time progresses. It’s also open source, with a substantial community, a grand number of plugins, and several helpful commentators.

Take my case as an example to inform your decision making on this issue. I am an interdisciplinary fellow with interests and expertise that span the arts and humanities, law and the social sciences, and computer science. As such, the note taking system that I’ve built does its best to (at least) accommodate these and (at best) allow them each to contribute to growth in the global complexity of thought I’m able to achieve. I also maintain a lively correspondence with a wide range of people who also try to address a similar set of knowledge management problems - at least, atmospherically similar, though the particular textures of their interests and goals may vary from each other and also from mine. Variety, however, is the spice of life, and I think that talking about my system with other people with different attitudes towards notes and different particular interests has allowed me to understand myself better and refine my system to better conform to my needs. This is probably what Tiago Forte means by ‘building a second brain.’

If you’ve read this far, I will assume you are open to trying out Obsidian. If so, I’ve included a few subsections below for you to consider when developing your personal knowledge management system. To illustrate how these ideas play out in practice, let’s consider Jade Law, a second-year law student looking to revamp her note-taking approach.

a. tags, links, and a dusting of organization

Jade is tired of using Google Drive to organize her notes. In the past, she would create a separate folder for each of her classes, and store her notes in a single, very large Google Doc outline, with readings and slides stored separately in the same folder. When exam time rolls around, she struggles to cross-reference her notes against each individual set of slides, and after the semester is done, the large Google Doc outline is hard to search and sits obliquely, ignored forever more. Within her outline, she would create headers by class date, and then she’d create a topical outline at the top of the document around exam time to re-arrange information best suited to prepare her for her final assessment.

Tired of this approach, she downloads Obsidian and creates a set of folders to cover cases, concepts, people, meetings, and class notes, see the image below. This is what I refer to as a ‘dusting of organization’ - a terminology I’m adapting from a particularly apt blog post by Joel Spolsky.

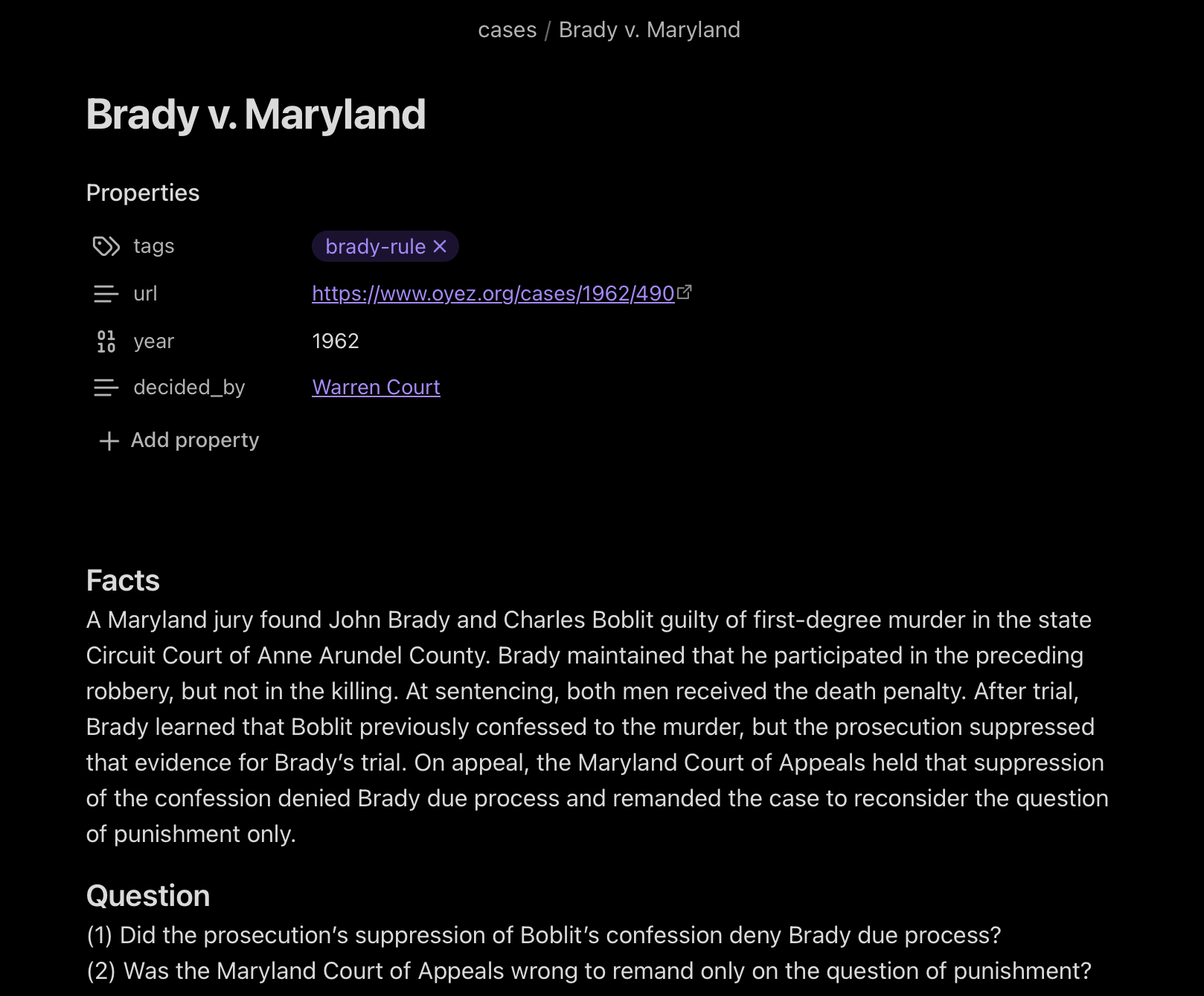

Just as soon as Jade has created this set of folders into which to sort her relevant notes and documents, she begins to break those barriers down by employing a set of tags and links to other files, so that the interlinks between different ideas can begin to manifest. For example, she begins writing a note on the Supreme Court case Brady v. Maryland for her criminal law course. In it, she adds a tag for the #brady-rule so that she can reference this idea in future notes. She also links the document to a separate note she’s previously written on the Warren Court, since she’d like to keep track of the cases she reads that were decided during that period. She adds this to the ‘frontmatter’ of the note by typing --- on the first line of her note on Brady v. Maryland, which opens an interface like the one you can see in the image below. She then adds a link by typing [[Warren Court]] into the field she’s created for this value, which creates a bi-directional link between two notes. This is another way in which this system allows her thinking to grow in complexity without necessarily increasing the complexity of managing the system itself.

Jade likes the idea of being able to read class slides and readings directly alongside the notes that she takes. To do this, she starts embedding these directly into the notes that she takes, as in the image below.

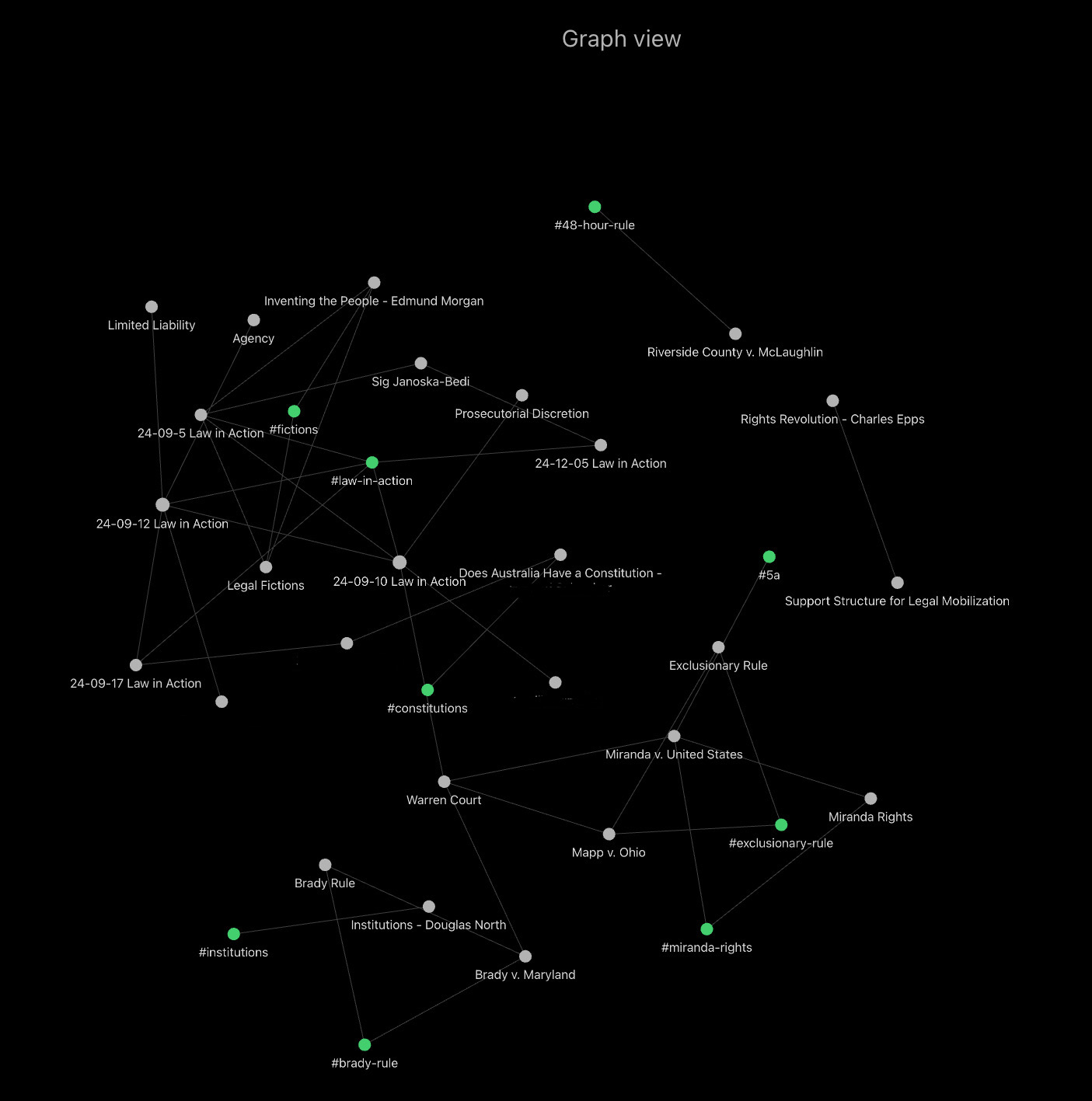

Around exam time, Jade can use an efficient keyword search for topics to track down more information from class - or other classes where she’s read similar cases. She can also use Graph View to plot out the interlinked ideas and tags from the various classes she has taken, as in the image below. This constellation view can be useful, or not - but there are other plugins like Dataview (referenced in a subsequent section) or Excalibrain that can extend this functionality significantly to assist with mind mapping around exam time.

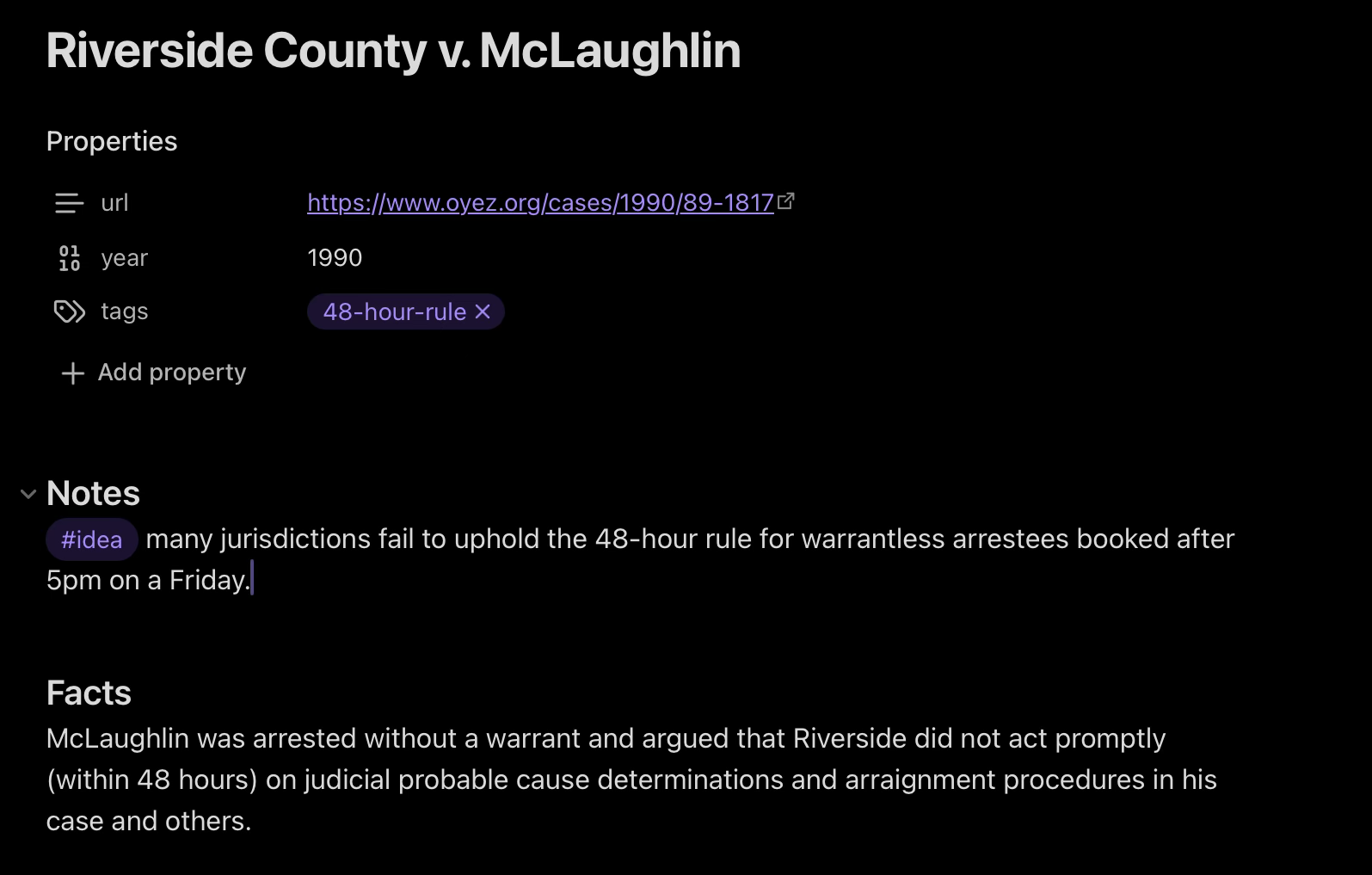

Jade will sometimes come up with a novel idea that she wants to follow up on later. When this happens, she’ll embed the #idea tag next to the idea, so that she can query for all her ideas later on, in case she wants to write more about it. I’ve included an example of this in the image below.

b. plugins, plugins, plugins

I generally recommend four basic plugins for Obsidian, which I’ve described at a high level below.

- Excalidraw. This is perhaps one of my favorite tools for building visualizations, charts, and drawings - which is saying a lot, as I’ve spent years using commercial options like Lucidchart and open source alternatives like Draw.io.

- File Tree Alternative. This is a better view of the folder structure that allows you to exclude certain folders from view, and also change how they are represented on the screen, see the first image above to get a sense of what this plugin looks like.

- Dataview. This is a system that allows you to run SQL-like queries against notes and their metadata, allowing you to generate eg. dynamic lists of notes that use a particular tag, meetings with a particular person, or notes written within a certain date range.

- Omnisearch. This is a much more powerful alternative to the default search feature, and allows you to get more out of your searches generally. Sometimes, when you use Obsidian with Git (more on this in a subsequent section), this plugin can force a file database reindex when the application starts up, which can take a few additional seconds.

The broader point, however, is that there is a whole universe of plugins that you’re able to choose from to extend the base functionality of Obsidian. One of the benefits of the system being open source is that the ecosystem is easy to extend. My claim here is that a notetaking application that cannot be easily extended is not really useful, because everyone has a different set of overarching concerns, aesthetic preferences, and configuration needs that necessitate customization. The Obsidian forum and commentators like Nicole van der Hoeven, both referenced earlier in this essay, are great resources for discovering new plugins. For the purpose of the hypothetical, we’ll say that Jade installs the four plugins listed above.

c. when to use dates in your note titles

I like to use dates in the title of some notes that I take that are ephemeral in nature - like a note from a particular day of class, or a specific meeting - because it makes it easy to keep the notes properly sorted by date when using alphanumeric sorting for a given folder view. It also makes it easier for me to navigate back to a given event using external temporal tools, like a calendar. That said, there are also permanent, conceptual notes that might be linked to multiple ephemeral notes, and which therefore warrants a name which does not contain a date but instead reflects the given topic. In Jade’s case, she chooses to prepend all her class and meeting notes with a date in the format of YYYY-MM-DD, but to have her case, people, and concept notes just follow the name of the subject of the note.

This distinction eventually grows more important when you have multiple notes referencing the same set of ideas, court cases, work products, or people. Eventually, you’ll want to develop a central collection point where you can dynamically list the content of the notes that meet some criteria. For example, let’s say Jade has a weekly meeting with a supervising professor as part of a research project she is completing for course credit. She might have a series of meetings where they discuss the topic of the research, and the work product she is completing to satisfy requirements to earn credit. She could choose to write these notes as ephemeral meeting notes, using a naming convention like “YYYY-MM-DD Professor Name” to name these files. She can then use tags, linked references, and tools like the Dataview plugin listed above to create permanent notes that consolidate all these ephemeral notes into a permanent location, ensuring a single point of reference and reducing confusion.

d. automate the boring stuff

A brief note about the following section

The following section includes advanced techniques and presumes the reader’s familiarity with basic programming principles and tools like the Python programming language and Git. Continue at your own peril.

Like Al Sweigart’s Automate the Boring Stuff with Python, the goal of this section is to provide some conventions and throwaway code snippets to help you automate some of the note management steps that, if done manually, take up precious time and mental resources. For example, it’s useful to generate groups of notes ahead of time when possible. For example, if you receive a course syllabus that lists the topics and readings for each day of class, then you can use that to generate a list of notes before the course even begins. This also reduces administrative complexity as the semester progresses by allowing you to create a structure of notes beforehand that you can fill in as you go. Let’s say you want to implement this using python. You can start by creating a dictionary of course dates, as in the snippet below. I typically use the class dates as keys for this dictionary, though you’re free to restructure this however you choose.

import datetime

import os

# Here we define the class days and assignment

class_days = {

"1/23/24": {

"description": "Constitutional challenges to eligibility restrictions",

"reading": "Read CB 98-104, 106-14 (through ¶ 3), 116-18 (¶ 6 only)"

},

...

}

Next, we will want to define a function to create a markdown file. We plan to pass it a handful of params, like the date string for a given class session, the contents of the dictionary we defined above, and then (optionally) links to the next and previous class, which we will use to create easy visual tools for cycling through class notes sequentially.

# Here we define a function to create the markdown file

def create_markdown_file(date_str, content, previous_class=None, next_class=None):

# This parses the date string and creates a datetime object

date = datetime.datetime.strptime(date_str, '%Y-%m-%d')

# This formats the datetime object from above into a string to use in the filename

filename = date.strftime(f'%Y-%m-%d Election Law.md')

# This portion handles the frontmatter for the markdown file we’re creating

markdown_header = f"""---

title: "{content['topic']}"

previous_class: "{f'[[{previous_class} Election Law]]' if previous_class else ''}"

next_class: "{f'[[{next_class} Election Law]]' if next_class else ''}"

tags:

- election-law

---

"""

# Here we construct the body of the markdown file, which just contains the description and the assignment

markdown_body = f"\n# {content['description']}\n\n**Assignment:**\n\n{content['reading']}\n\n"

# Finally, we write the frontmatter and body to the markdown file

with open(filename, 'w') as file:

file.write(markdown_header)

file.write(markdown_body)

To implement this function for each class identified in the class_days dictionary above, we can run the following logic:

# We sort the dates sequentially

previous_class = None

sorted_dates = sorted(class_days.keys())

# Then we iterate through each item in the now-sorted dictionary

for i, date_str in enumerate(sorted_dates):

# This is the content of a given day

content = class_days[date_str]

# Here we define the next class date if there is one

next_class = sorted_dates[i + 1] if i + 1 < len(sorted_dates) else None

# Now, we run the function we defined above for the class date that we’re on

create_markdown_file(date_str, content, previous_class, next_class)

# For the next iteration, we set the date from the current iteration to the

# previous_class date for the next iteration... pretty nice, huh?

previous_class = date_str

Add this all together, et voilà. You have a list of classes for your entire semester of election law. Not only that, but you have the readings and topic pre-loaded, though you mileage may vary since some professors will sometimes make changes to these parts of the class as the semester progresses. Additionally, the next_class and previous_class elements will show up in the frontmatter of your notes and allow you to cycle through class date sequentially, which can be a substantial quality-of-life improvement.

If you want to back up your application, I recommend using a Git repository, and suggest using Github specifically to host your notes. Other commentators can provide better instructions than I can on how to implement this, but I’ll note that there are Obsidian plugins that help facilitate automatic synchronization of your local Obsidian vault with the remote repository that you’ve backed it up to. If you’re using the iOS app, I recommend using Working Copy. The pro version of Working Copy is free for students who are part of the Github developer program, at least as of March, 2025, and it comes with some useful Shortcuts for you to automate synchronization just like you can do with the desktop application.

e. conclusions, etc

I won’t expound too greatly on the great successes that Jade finds after law school, no doubt a direct result of her excellent and well-considered method for managing knowledge. I will, however, take a little bit of space to reflect on how she has positioned herself. Notes are not useful unless they can be understood within the contexts they were intended to serve. What I mean is that a note written for your future self is not useful unless it’s configured so that your future self can understand it; likewise, for notes written to accomplish short-run goals. A dusting of organization using high level folders, a standard naming convention, and even a set of common subheaders for certain categories of notes (eg. always having Facts, Question, Holding, and Analysis headers for notes corresponding to legal cases) can keep things predictable and reduce the complexity of your notes and the time it takes to manage them, and allow you to accomplish both short- and long-run intellectual goals. This way of structuring notes today can position Jade to earn excellent grades and, later, to succeed in a top law firm or competitive judicial clerkship where she needs to be able to wrap her head around a wide range of complicated topics on tight timeframes. Likewise, other future-oriented practices, like using an #idea tag to designate novel ideas as you take notes, can situate you to exploit intellectual opportunities later in life, when time and expertise might permit the writing of an academic journal article or to take some other action on a topic of interest from your school days. So, if you’ve read this far, I earnestly hope - all the more so if you are one of my students - that you take this as an opportunity to think about what your goals are in writing notes and, if you feel like now is a good time to reconsider the systems you build around those goals, that you use this essay as a resource to do so.